I had previously written about my experience flying from Albuquerque to Houston and how I was able to overcome confirmation bias in getting through security and making my flight after a long security checkpoint shutdown.

On the ensuing flight, I was reading an article by Ben Yagoda in The Atlantic about cognitive biases. I was most interested in this article, partly because I talk about these biases in my teaching at banking schools and in keynotes, but mostly due the excellent content that my good friend Lee Wetherington produces on this subject. The more I feel that I am able to combat confirmation bias, I am subject to the anchor bias in which I am more likely to believe that I am less susceptible to cognitive biases than I actually am.

In Yagoda’s excellent article, the following problem was presented:

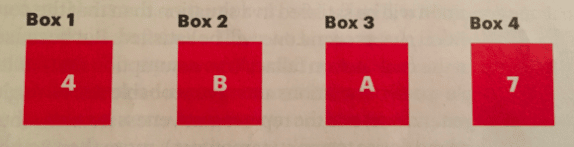

Below are 4 cards. They are randomly chosen from a deck of cards in which every card has a letter on one side and a number on the other side. Your task is say which of the cards you need to turn over in order to find out whether the following is true or false. The rule is, “If a card has an ‘A’ on one side, then it has a ‘4’ on the other side.” Turn over only those cards you need to check the rule.

(a) Box 3 only

(b) Boxes 1, 2, 3 and 4

(c) Boxes 3 and 4

(d) Boxes 1, 3 and 4

(e) Boxes 1 and 3

What is your answer? Because of confirmation bias, most people will choose answer (e). And in fact, while I was reading the article, that is the choice I made. But the correct answer is (c). And I was so ready to believe that I had confirmation bias licked! Even after reaching an article that was alerting me to be looking out for these biases, I still choose answer (e). I figured that I had to turn over the “4” card to make sure there was an “A” on the other side. But if you read the instructions carefully, it only requires that A cards have a “4”. Nothing said that any other letter could not also have a “4.” I failed to get it right because my bias was that all “A”s would have “4”s and all “4”s would have “A”s.

So what? No harm done in making a mistake while reading an article on a flight, right? But, the confirmation bias has a negative impact in the real world. When we assume that what we already know is true, we tend to ignore all other evidence to the contrary. In fact, it is more likely that we would take any evidence that we encounter and reshape it into the image of what we had already decided is true.

From an innovation standpoint, confirmation bias is what leads us to throw out potential game-changing ideas as ridiculous or insane.

It might be disheartening for you to know that there are many behavioral scientists that believe that there is no way to overcome our biases. And they may be right. But, I believe that like any other skill, we can make a change in how we behave if we a) recognize that the bias exists, b) are aware of the types of circumstances where it most often manifests, and c) are self-aware enough to admit that we may be making an error related to a behavioral bias.

Once you overcome a bias one time, it becomes easier to recognize that same bias in a similar situation again. Also, if you have close friends with whom you regularly interact, ask them to be aware of when you might be acting out of bias and empower them to call you out on it. Limiting the negative effects of behavioral bias like the confirmation bias may just be the key to unlocking your true innovative potential.